This weekend, I made a trip to the New York installment of The European Fine Art Fair (popularly known as TEFAF). I wanted to share my takeaways from an event I genuinely very much enjoyed and one I see as an important indicator of issues at play in the art market at large.

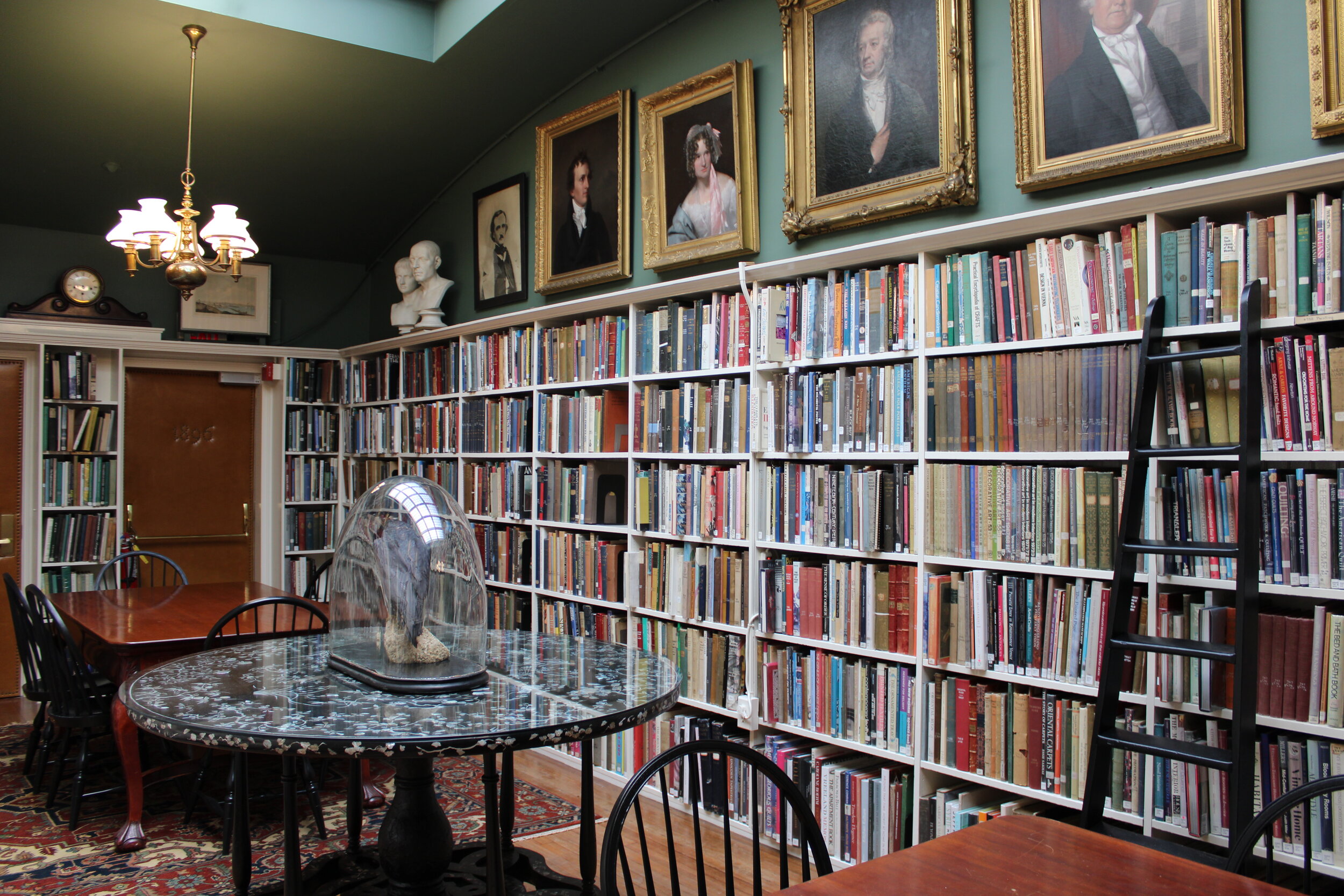

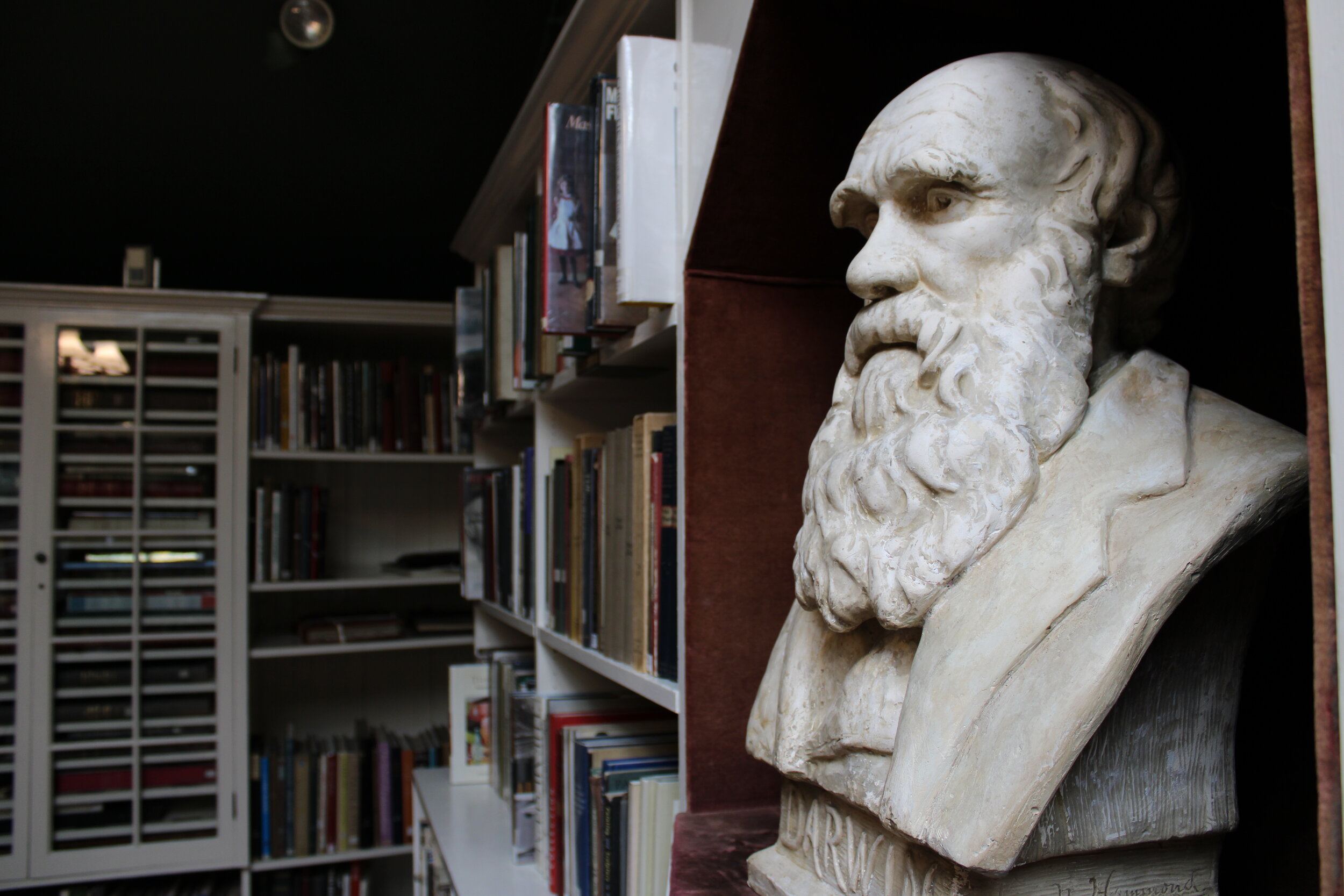

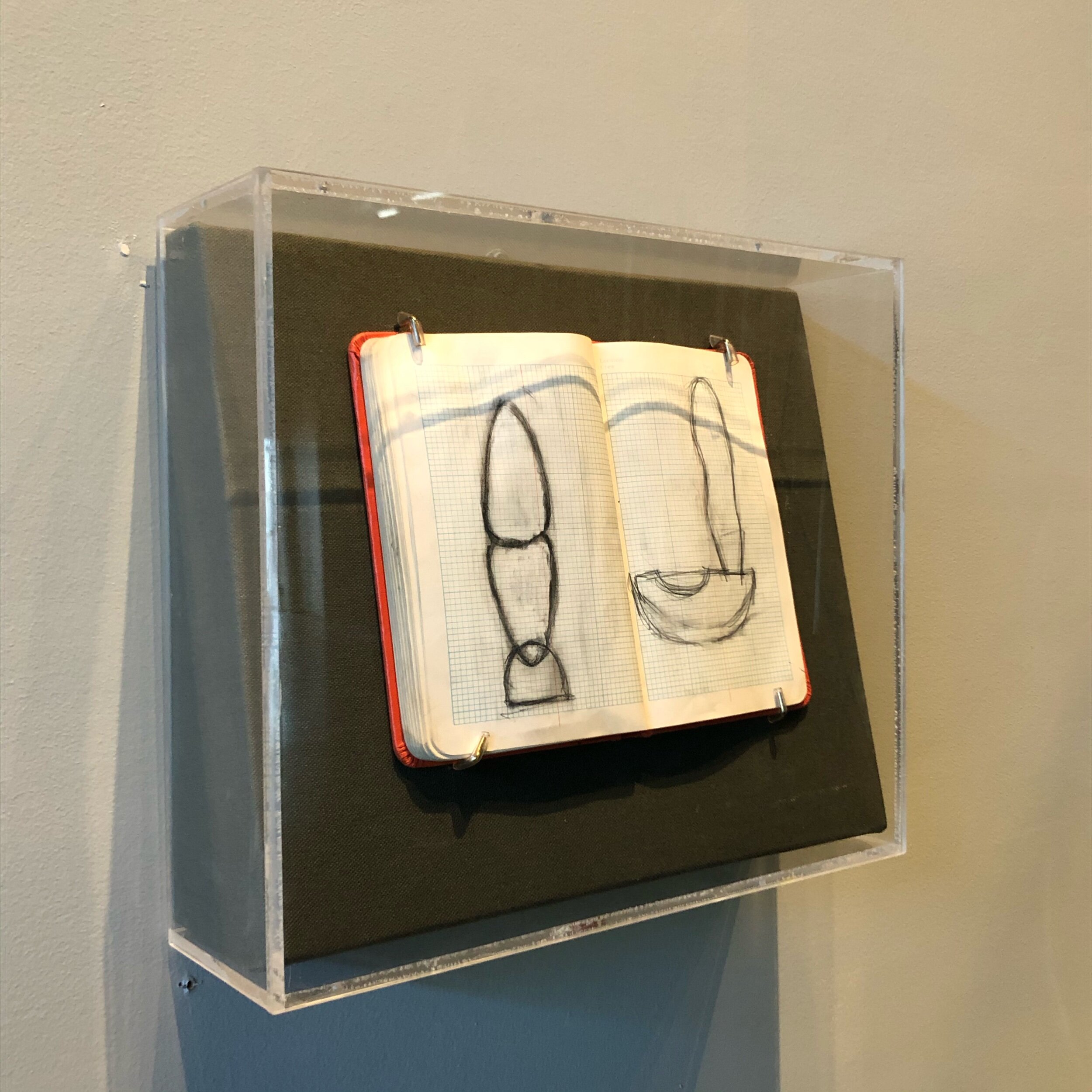

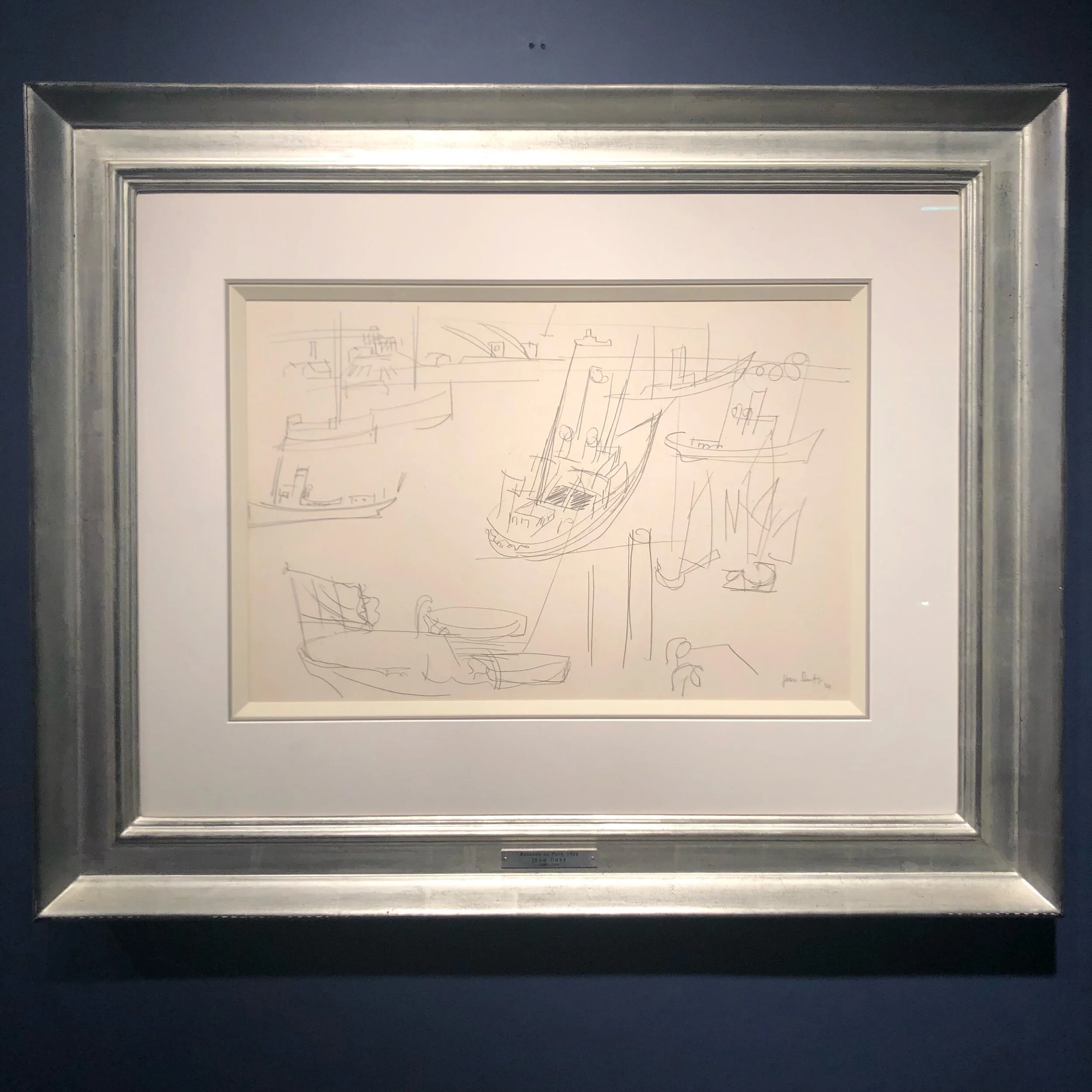

Held in the Seventh Regiment Park Avenue Armory, itself a relic of a bygone type of elegance, the The European Fine Art Fair’s (TEFAF) Fall Installment includes galleries specializing in fine and decorative arts dated prior to 1920 and primarily from Europe and the United States. First mounted in 1988 and now hosted three times a year (once in Maastricht in the Netherlands and twice in New York City), the show follows the art fair model it helped to popularize. Galleries and art dealers rent individual booths and exhibit a selection of works drawn from their regular inventory, or new discoveries shown for the first time. The participating exhibitors are vetted in advance as a form of quality control and the Fair’s website boasts a preponderance of museum quality objects. The resulting event features work ranging widely, from drawings by Egon Schiele and Le Corbusier, to Old Master paintings, as well as Ancient and Classical sculpture. The fall iteration of TEFAF is known for featuring older, and potentially more traditional, work whereas the spring show is focused on more modern objects. This show is truly a place to see some of the finest artworks available in retail environments up close and also to examine the workings of an art market in transition.

To say that TEFAF is a refined experience would be an understatement. A visit to the show requires an admission fee more expensive than any museum and most of the visitors are dressed well enough to make it difficult to distinguish collector from dealer. There is something decidedly old world about it and decidedly old school, too. Fitted out in bespoke suits and designer garments, an army of dealers and assistants charm serious connoisseurs and collectors or merely those morbidly curious enough to spend $55 and the better part of a Saturday looking at beautiful things that, barring a bank heist, they will never be able to afford. In addition to crossing paths with a stunning Picasso or two, one is also bound to come in contact with what F. Scott Fitzgerald called “the consoling proximity of millionaires”.

It all feels slightly of another time. Most of the artworks on offer at TEFAF would not have been out of place in the homes of popes or princes, Romanovs or Bourbons. Reviewing the provenance on some object labels, it is not at all uncommon to find a former famous owner or a previous place in a great collection. The contemporary titans of finance or tech who are able drop a cool million on a painting here are not far off from Gilded Age patrons like Henry Clay Frick or J.P. Morgan, who would have delighted in such an event and undoubtedly would have greedily used it to add to their own hoards as well.

This show largely remains the domain of this same archetypal self-assured collector, but one occasionally can spot the unmistakeable look of an art advisor dragging nouveau riche clients through booths of artworks which they do not necessarily appreciate. The phrase “no, Jackson Pollock is much later than this…” might be overheard, or so too an admonishment about manners that, in another generation, were seen as de rigueur. A business degree from Syracuse is as likely an attribute now as one in art history from the Sorbonne. But, it is still a deeply worldly event, where guests in line for the Fair’s restaurant chat languidly in German, French, or Italian. As I walk by, two Japanese women in traditional Kimono are seen in by a maître d’.

Behind all of this old and new international glamour, though, it is worth noting the audible whispers of Brexit and the unsightly murmurs of “return on investment”. It is now unavoidable as ever for art, regardless of age or genre, to be seen and used as a financial tool, and one which is tied inextricably to the fickle fortunes of complex and global systems. As much as taste and quality can determine value, so too can a myriad of other factors, which are speedily defined and redefined in terms far removed from the theoretical values of the art world. There is an incestuous tangle between financial and political power brokers and the art dealers who remain dependent on their patronage, while also being impacted by the workings of economies over which these king-makers often hold some sway.

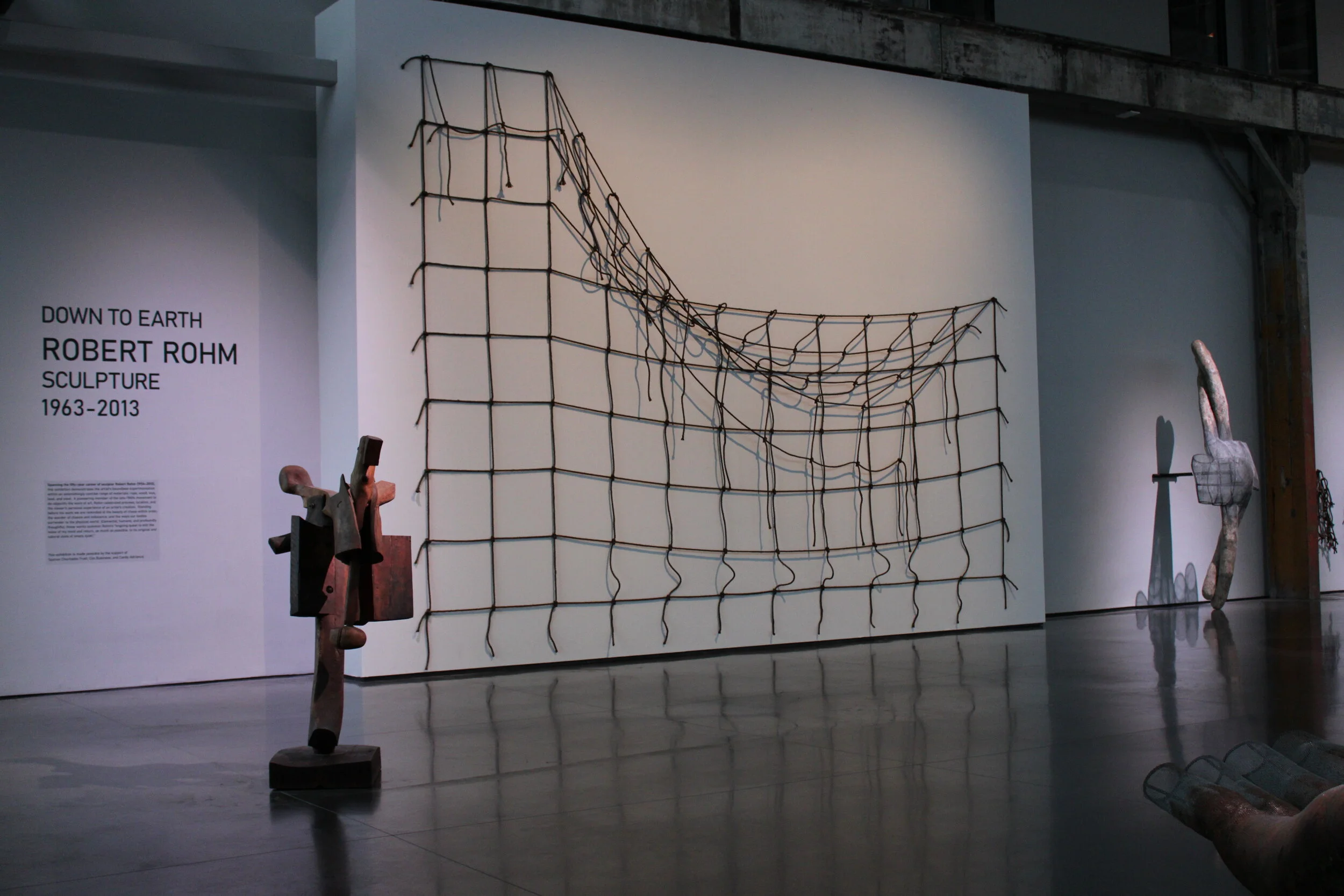

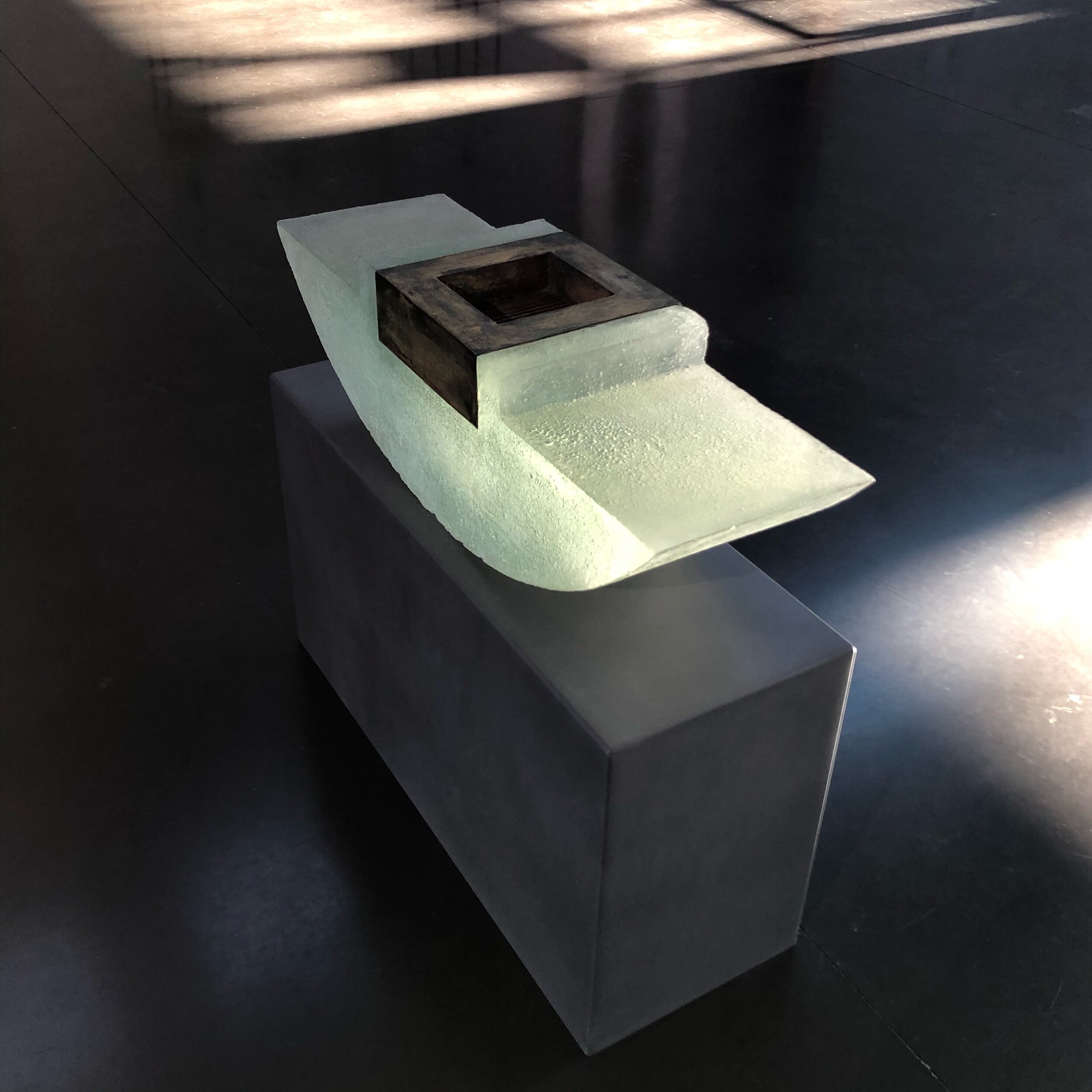

Although the Fall Installment of TEFAF primarily focuses on objects prior to 1920, errant contemporary items find their way in, mostly through specialty collaborations. It must be said that there is something a little inelegant about a Fontana next to a fine Classical sculpture, or a Warhol adjacent to a Bonnard - something of the whiff of defeat. Dealers and gallerists formerly full of confidence in the market for artworks now seen in some quarters as a little too conventional are finding themselves engaging with the red hot objects of the Modern and Contemporary market in order to buoy their fortunes. The veneer of a fictional well-rounded and broadly interested collector is applied to a decision that is one of purely economic necessity. The market is changing and so too are buyers’ interests. If the pairings that result from these real world realties seem a little odd, they are also easily understandable. A commercial gallery is a business after all, not a religion.

Such is the world today. Gallerists are attempting to make an argument that eighteenth century continental portraiture or medieval polychrome sculpture can be as exciting a proposition as a Basquiat. It remains to be seen if their tactics will be fruitful, or if the one-to-one comparison between newer and more avant-garde objects with their elders will serve only to illustrate the retrograde aspects of the latter to a new generation of collectors more interested in the art and design of the mid-twentieth century than that of the Middle Ages.

All of these details add to the intrigue of TEFAF. It is, indeed, a place to see exceptional things from some of the best dealers in the world. It is also a place to rub shoulders with the art world literati on duty: a curator from the Metropolitan photographing a piece with their phone, a museum official negotiating a deal with a seller, a prominent collector using emphatic, and course, language to describe a dealer’s prices. These details, this vague camaraderie, point to the ways in which the Fall iteration of TEFAF also harkens back to a time when the art world was far less complicated than it is now.

A booth near the entrance of the Fair features a Venitian scene by Bellotto mounted on a partition wallpapered in rich blue velvet. One cannot help but imagine a time when pedigreed art aficionados invited similarly pedigreed collectors into private rooms nearly identically accoutered. Over old cigars and older scotch, sales were ironed out and relationships were built. Of course, such appointments, slightly altered, still take place in the converted townhouses of the Upper East Side, or in the fine interiors of St. James’s in London, or in still more fashionable corners of Berlin or Zurich, Paris or Rome. But now these rarified dealers are working publicly too, on a world stage, and in an art market that is being radically remade by the modern, the new, and the digital.

While TEFAF definitely represents long-standing values of vetting and connoisseurship along with a seriousness of research, purpose, and quality, it is unclear if the Fall show can also represent a future that is largely defined by the excitement around Modern and Contemporary, or by art as financial asset, as investment, as collateral, as splashy, if hollow, political activism.

TEFAF is a preeminent art event and a place to see beautiful things, important things, things that are of rare and spectacular quality. It also will be a place of importance as a testing ground for market realities and one of many barometers measuring the tastes and trends within a labyrinthine, globalized art economy.

The next installment of The European Fine Art Fair (TEFAF) will focus on Modern and Contemporary Art and Design and will take place May 8-12, 2020 at the Park Avenue Armory.

To learn more, visit tefaf.com.